Tags

Happy Birthday Djuna Barnes

Djuna Barnes (June 12, 1892 – June 18, 1982) was an American writer who played an important part in the development of 20th century English language modernist writing and was one of the key figures in 1920s and 30s bohemian Paris after filling a similar role in the Greenwich Village of the teens. Her novel Nightwood became a cult work of modern fiction, helped by an introduction by T. S. Eliot. It stands out today for its portrayal of lesbian themes and its distinctive writing style. As a roman à clef, the novel features a thinly veiled portrait of Barnes in the character of Nora Flood, whereas Nora’s lover Robin Vote is a composite of Thelma Wood and the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. Since Barnes’s death, interest in her work has grown and many of her books are back in print.

Paris (1921–1930)

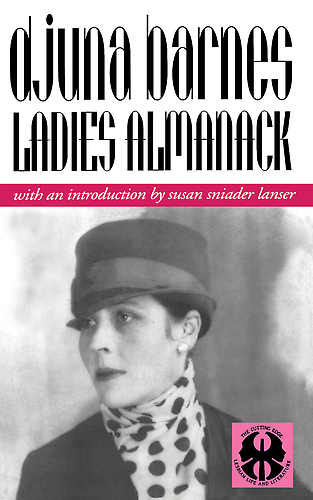

In the 1920s, Paris was the center of modernism in art and literature; as Gertrude Stein remarked, “Paris was where the twentieth century was.”Barnes first traveled there in 1921 on an assignment for McCall’s Magazine. She interviewed her fellow expatriate writers and artists for U.S. periodicals and soon became a well-known figure on the local scene; her black cloak and her acerbic wit are remembered in many memoirs of the time. Even before her first novel was published, her literary reputation was already high, largely on the strength of her story “A Night Among the Horses,” which was published in The Little Review and reprinted in her 1923 collection A Book. She was part of the inner circle of the influential salon hostess Natalie Barney, who would become a lifelong friend and patron, as well as the central figure in Barnes’s satiric chronicle of Paris lesbian life, Ladies Almanack. They probably also had a brief affair, but the most important relationship of Barnes’s Paris years was with the artist Thelma Wood. Wood was a Kansas native who had come to Paris to become a sculptor, but at Barnes’s suggestion took up silverpoint instead, producing drawings of animals and plants that one critic compared to Henri Rousseau. By the winter of 1922 they had set up housekeeping together in a flat on the Boulevard Saint-Germain. Another close friendship that developed during this time was with the Dada artist Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, with whom Barnes began an intensive correspondence in 1923. “Where Wood gave Barnes a doll as a gift to represent their symbolic love child, the Baroness proposed an erotic marriage whose love-child would be their book.” From Paris, Barnes supported the Baroness in Berlin with money, clothing, and magazines. She also collected the Baroness’s poems and letters.

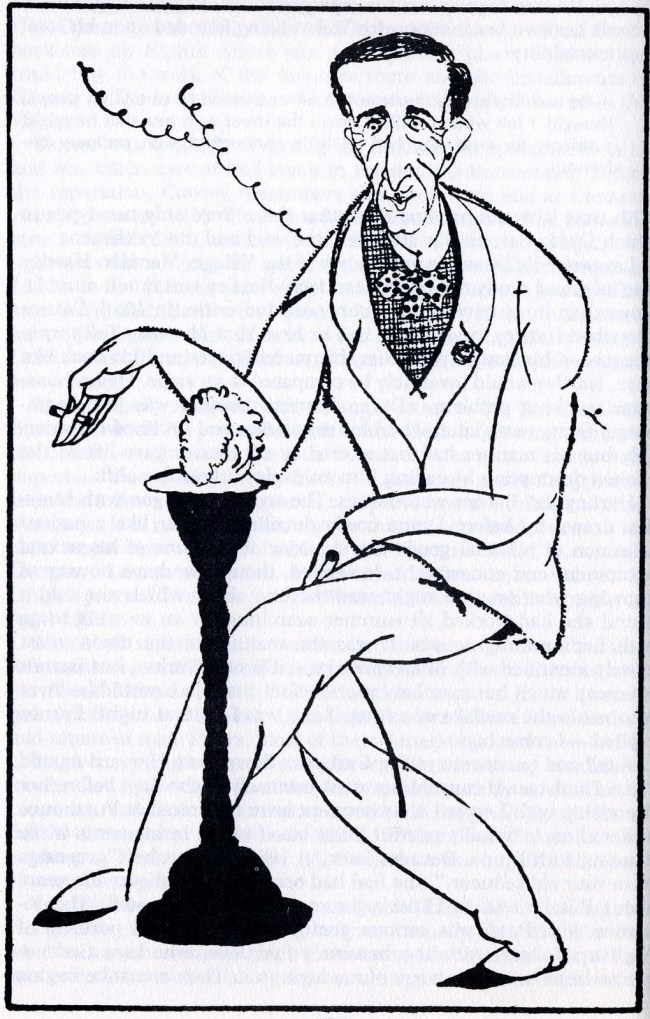

Barnes’s drawing of James Joyce illustrated her 1922 interview with him inVanity Fair.

Barnes arrived in Paris with a letter of introduction to James Joyce, whom she interviewed for Vanity Fair and who became a friend. The headline of her Vanity Fair interview billed him as “the man who is, at present, one of the more significant figures in literature,” but her personal reaction to Ulysses was less guarded: “I shall never write another line…. Who has the nerve to after that?” It may have been reading Joyce that led Barnes to turn away from the late 19th century Decadent and Aesthetic influences of The Book of Repulsive Women toward the modernist experimentation of her later work. They differed, however, on the proper subject of literature; Joyce thought writers should focus on commonplace subjects and make them extraordinary, while Barnes was always drawn to the unusual, even the grotesque. Then, too, her own life was an extraordinary subject. Her autobiographical first novel Ryder would not only present readers with the difficulty of deciphering its shifting literary styles—a technique inspired by Ulysses—but also with the challenge of piecing together the history of an unconventional polygamous household, far removed from most readers’ expectations and experience.

Despite the difficulties of the text, Ryder’s bawdiness drew attention, and it briefly became a New York Times bestseller. Its popularity caught the publisher unprepared; a first edition of 3,000 sold out quickly, but by the time more copies made it into bookstores, public interest in the book had died down. Still, the advance allowed Barnes to buy a new apartment on Rue Saint-Romain, where she lived with Thelma Wood starting in September 1927. The move made them neighbors of Mina Loy, a friend of Barnes’s since Greenwich Village days, who appeared inLadies Almanack as Patience Scalpel, the sole heterosexual character, who “could not understand Women and their Ways.”

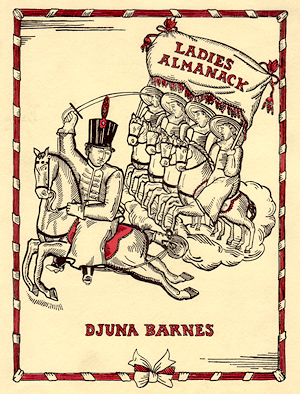

Due to its subject matter, Ladies Almanack was published in a small, privately printed edition under the pseudonym “A Lady of Fashion.” Copies were sold on the streets of Paris by Barnes and her friends, and Barnes managed to smuggle a few into the United States to sell. A bookseller, Edward Titus, offered to carry Ladies Almanack in his store in exchange for being mentioned on the title page, but when he demanded a share of the royalties on the entire print run, Barnes was furious. She later gave the name Titus to the abusive father in The Antiphon.

Barnes dedicated Ryder and Ladies Almanack to Thelma Wood, but the year both books were published—1928—was also the year that she and Wood separated. Barnes had wanted their relationship to be monogamous, but had discovered that Wood wanted her “along with the rest of the world.” Wood had a worsening dependency on alcohol, and she spent her nights drinking and seeking out casual sex partners; Barnes would search the cafés for her, often winding up equally drunk. Barnes broke up with Wood over her involvement with heiress Henriette McCrea Metcalf (1888–1981), who would be scathingly portrayed in Nightwood as Jenny Petherbridge.

1930s

Much of Nightwood was written during the summers of 1932 and 1933, while Barnes was staying at Hayford Hall, a country manor in Devonshire rented by the art patron Peggy Guggenheim. Fellow guests included Antonia White, John Ferrar Holms, and the novelist and poet Emily Coleman. Evenings at the manor—nicknamed “Hangover Hall” by its residents—often featured a party game called Truth that encouraged brutal frankness, creating a tense emotional atmosphere. Barnes was afraid to leave her work in progress unattended because the volatile Coleman, having told Barnes one of her secrets, had threatened to burn the manuscript if Barnes revealed it. But once she had read the book, Coleman became its champion. Her critiques of successive drafts led Barnes to make major structural changes, and when publisher after publisher rejected the manuscript, it was Coleman who pressed T. S. Eliot, then an editor atFaber and Faber, to read it.

Faber published the book in 1936. Though reviews treated it as a major work of art, the book did not sell well. Barnes received no advance from Faber and the first royalty statement was for only £43; the U.S. edition published byHarcourt, Brace the following year fared no better. Barnes had published little journalism in the 30s and was largely dependent on Peggy Guggenheim’s financial support. She was constantly ill and drank more and more heavily—according to Guggenheim, she accounted for a bottle of whiskey a day. In February 1939 she checked into a hotel in London and attempted suicide. Guggenheim funded hospital visits and doctors, but finally lost patience and sent her back to New York. There she shared a single room with her mother, who coughed all night and who kept reading her passages from Mary Baker Eddy, having converted to Christian Science. In March 1940 her family sent her to a sanatorium in upstate New York to dry out. Furious, Barnes began to plan a biography of her family, writing to Emily Coleman that “there is no reason any longer why I should feel for them in any way but hate.” This idea would eventually come to fruition in her play The Antiphon. After she returned to New York City, she quarreled bitterly with her mother and was thrown out on the street.

Left with nowhere else to go, Barnes stayed at Thelma Wood’s apartment while Wood was out of town, then spent two months on a working ranch in Arizona with Emily Coleman and Coleman’s lover Jake Scarborough. She returned to New York and, in September, moved into the small apartment at 5 Patchin Place in Greenwich Village where she would spend the last 42 years of her life. Throughout the 40s she continued to drink and wrote virtually nothing. Guggenheim, despite misgivings, provided her with a small stipend, and Coleman, who could ill afford it, sent US$20 a month (about $310 in 2011). In 1946 she worked for Henry Holt as a manuscript reader, but her reports were invariably caustic and she was soon fired.

In 1950, realizing that alcoholism had made it impossible for her to function as an artist, Barnes stopped drinking in order to begin work on her verse play The Antiphon. The play drew heavily on her own family history, and the writing was fueled by anger; she said, “I wrote The Antiphon with clenched teeth, and I noted that my handwriting was as savage as a dagger.” When he read the play, her brother Thurn accused her of wanting “revenge for something long dead and to be forgotten,” but Barnes, in the margin of his letter, described her motive instead as “justice,” and next to the word dead he wrote, “not dead.”

After The Antiphon Barnes returned to writing poetry, which she worked and reworked, producing as many as 500 drafts. She wrote eight hours a day despite a growing list of health problems, including arthritis so severe that she had difficulty even sitting at her typewriter or turning on her desk lamp. Many of these poems were never finalized and only a few were published in her lifetime.

During her Patchin Place years, Barnes became a notorious recluse, intensely suspicious of anyone she did not know well. E. E. Cummings, who lived across the street, would check on her periodically by shouting out his window, “Are you still alive, Djuna?” Bertha Harris put roses in her mailbox, but never succeeded in meeting her; Carson McCullers camped on her doorstep, but Barnes only called down, “Whoever is ringing this bell, please go the hell away.” Anaïs Nin was an ardent fan of her work, especially Nightwood. She wrote to Barnes several times inviting her to participate in a journal on women’s writing, but received no reply. She remained contemptuous of Anaïs and would cross the street to avoid her. Barnes was angry that Nin had named a character Djuna, and when the feminist bookstore Djuna Books opened in Greenwich Village, Barnes called to demand that the name be changed. Barnes had a lifelong affection for poet Marianne Moore since she and Moore were young in the 1920s. Barnes was bitter at the end, but underneath her sometimes formidable facade she was warm and always amusing, with an almost Shakespearean vocabulary (despite having not had much formal education).

Although Barnes had other female lovers, in her later years she was known to claim, “I am not a lesbian; I just loved Thelma.”

Barnes was elected to the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1961. She was the last surviving member of the first generation of English-language modernists when she died in New York in 1982.

So stylish!

LikeLike

I agree!

Isn’t she just divine?

And sooooo unashamedly pissed off! I just love her!

LikeLike

Are you sure that the picture of Branger is a picture of Solita SOlano and DJuna Barnes?

This picture is from 1925 so Djuna Barnes was 32 years old in 1925 ( if im not wrong)and the woman on the picture looks much younger than 32 years old

And Djuna Barnes on profile does not have the same nose than the woman on the picture of Branger .

How do you know it’s DJuna Barnes ?

I really like this picture I’ve tried to find out who were these women .

.

LikeLike

No… I think you might be right. I can’t find my original source on that pic now.

I’ve taken it out.

Thanks for the heads up.

L.

LikeLike